A little later than planned, and with a change of cast: the chiffchaffs have started singing in the south of England over the past few days, so we’re tuning in to this herald of spring. The starling will follow at the weekend. Thanks for your patience. ~ Charlie

For many of us, that first moment in the year that we hear this song makes for a memorable day.

Perhaps those two notes aren’t a thriller on their own. But they signify something dear to our hearts, because chiffchaffs are among the very first summer birds to migrate back to Britain.

Like cuckoo and curlew, this is a bird whose name in English is a direct description of the song - ‘chiff-chaff, chiff-chaff’.

It’s not far away from the ‘squeaky bicycle pump’ of the great tit, but the rhythm is less mechanical, sometimes a little wonky.

From time to time chiffchaffs like to double or triple one of the notes, or reverse the order.

They also have an odd little churr, lower and quieter than the ‘chiff-chaff’ notes, which they make in the gaps between. Like they’re keeping their engine turning over.

Chiffchaffs winter closer to Britain than many species of warbler, meaning their migration is relatively short - up from North Africa or the Mediterranean. This enables them to arrive ahead of the pack.

This relatively short migration is reflected not only in their early arrival, but in their very feathers.

Famously, chiffchaffs look extremely similar to one of our other most common summer visitors, the willow warbler. Willow warblers spend their winters much further south, in sub-Saharan Africa, and tend not to return here until early April.

Telling a willow warbler from a chiffchaff by song is easy enough - the willow warbler uses so many notes in its descending stream that you can’t help but feel it’s rubbing the chiffchaff’s nose in it.

Telling a willow warbler from a chiffchaff on looks alone is trickier. One indication, though, is that the chiffchaff’s wings are shorter - they just don’t need to travel so far on them.

Less and less far, perhaps. The chiffchaff’s status as the first summer-visiting songbird has been muddied in recent years, because a thousand or so spend the winter with us.

It’s thought that most of these birds breed further north in the summer, within Britain or in Scandinavia, and have found that they don’t need to migrate all the way to southern Europe to survive the colder months.

These wintering individuals typically hang out in the more glamorous locations, such as sewage works and flooded gravel pits, where there are reliable supplies of small insects. They are also seen from time to time in gardens and the wider countryside.

And on a warm spring day these wintering birds may be tempted to sing. So it’s not easy to be sure that you’re listening to a genuine summer arrival if you hear one at the end of February or early March.

However, most of those birds we hear in the second and third week of March are likely to be fresh arrivals, and they do arrive all of a sudden. It may be that there are no chiffchaffs singing and then the following week there are two, three, four in a small area.

And of course they’re most welcome at this time of year. It’s not always feeling springlike, but the chiffchaff reassures us that change can’t be too far around the corner.

Ospreys, via gulls

Another imminent summer migrant, though one perhaps more often seen than heard, is the osprey. Having wintered in West Africa, they can be back on their ancestral nest sites early in March.

With around 300 pairs now breeding in the UK, and other young birds summering, the chances of one flying over your head in early spring are rather less remote than they were a few decades ago.

At this time a ‘gull alarm’ can help you find an osprey.

Gulls react strongly to a passing osprey, leaping into the air and making a lot of noise together. So it’s always worth checking what the fuss is about.

Watch out for a large, bow-winged bird, pale underneath, with chocolate-coloured edges, heading purposefully (typically) to the north.

Or keep an eye on the Loch of the Lowes webcam, back up and running for its 25th year in 2024. It’s a wonderful place to watch for their return, and to listen to other birds of the Scottish Highlands while you’re waiting.

Thanks for reading and listening. This is the ninth instalment in 2024’s cycle of Shriek of the Week. You can catch up with Collared Dove, Wren, Dunnock, Great Spotted Woodpecker, Robin, Great Tit, Song Thrush and Blackbird (the last includes an explanation of how this all works in 2024).

For those in a position to do so, taking out a paid subscription to Shriek of the Week supports me to write more and improve what I do. It also gets you an invite to our livestream odyssey Early Bird Club call, and discounts to some in-person events in the UK.

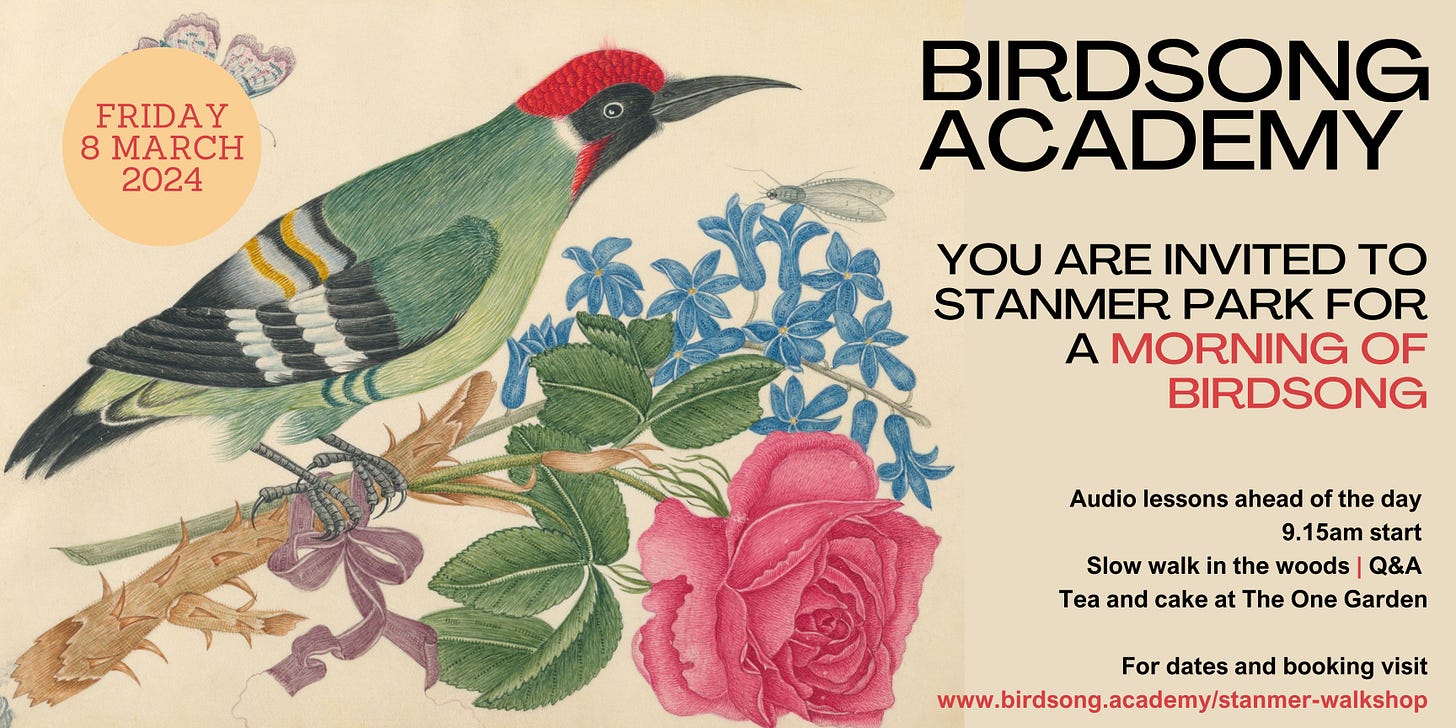

Our first real-world event of the year is this Friday, 8 March in the bird-rich woodland of Stanmer Park on the outskirts of Brighton. We’ll hope to find firecrests, woodpeckers, finches, treecreepers, nuthatches and wagtails, and we will definitely locate cake at the One Garden cafe.

More details of this and other upcoming walkshops on the Birdsong Academy website.

Find more birds by ear in 2024 with Birdsong Academy:

British Birdsong Essentials - the 10-week course - just about still time to join up before the first live practice session on Thursday 7th March. Lower cost options are available too - see a recent Shriek for details.

Up With The Birds dawn chorus calls (free, April & May)

Media credits:

Thanks to the British Library and Lawrence Shove for the audio

Chiffchaff image by Kathy Büscher from Pixabay

Share this post