Our tiniest bird has an equally tiny scene to remember its song by.

Imagine the dinkiest of bicycles, wheels in need of a good oiling, running down a slope and falling over at the bottom.

If that’s a bit of a stretch, ‘needly needly needly needly’ is a useful approximation for rhythm too.

This has the advantage of alluding to where you’re likely to hear a goldcrest too: anywhere with pine needles.

That might be deep in the Caledonian forest, or among the skirts of an ancient yew tree. But equally it could be in your neighbour’s half-dead leylandii hedge. They’re not fussed.

The pitch of the goldcrest’s song, and its other silvery little vocalisations, means that it can be hard to pick up for some human ears.

Fortunately goldcrests are not shy, often feeding a few feet from the ground, sometimes close to busy paths and roads. With a little patience, or luck, one will jump to the end of a nearby branch at eye level, and hang upside down, hover or generally fidget, unbothered by your presence.

When the angle’s right, you will see the fleck of fiery orange or gold feathers, bordered by dark lines, running along its crown. Occasionally, typically during an argument, these lift to form a crest.

Goldcrests are resident across Britain, and singing already. Now’s a good time to pick them out, before much of the spring chorus has begun.

Fantasy hitchhikers

With such tiny bodies, weighing just a few grams, they can struggle to keep fuelled up in long periods of cold weather. But goldcrests are hardy adventurers.

In the autumn, thousands arrive from the East to winter here, and the unlikelihood that something so small could make it across the North Sea led early observers to some creative theories.

Most famous is the idea that they hitch a ride on the back of woodcocks, which arrive at about the same time.

This is now in the same category as the notion that swallows spend the winter hibernating in ponds, but the lengths we have gone to explain these phenomena does serve to underline just how extraordinary the realities of migration really are.

Goldcrests are found throughout Europe and across much of Asia, as far east as Japan. Closely related species in the Americas are known as kinglets.

See also (with luck): Firecrest

Until very recently, the goldcrest’s swish cousin the firecrest was a scarce species on the very edge of its range in Britain. No longer. Firecrests are well established in the south-east, and becoming more regular further north and west, to be found in mixed woodlands, parks, churchyards and big gardens. Their song is a simple accelerating series of notes.

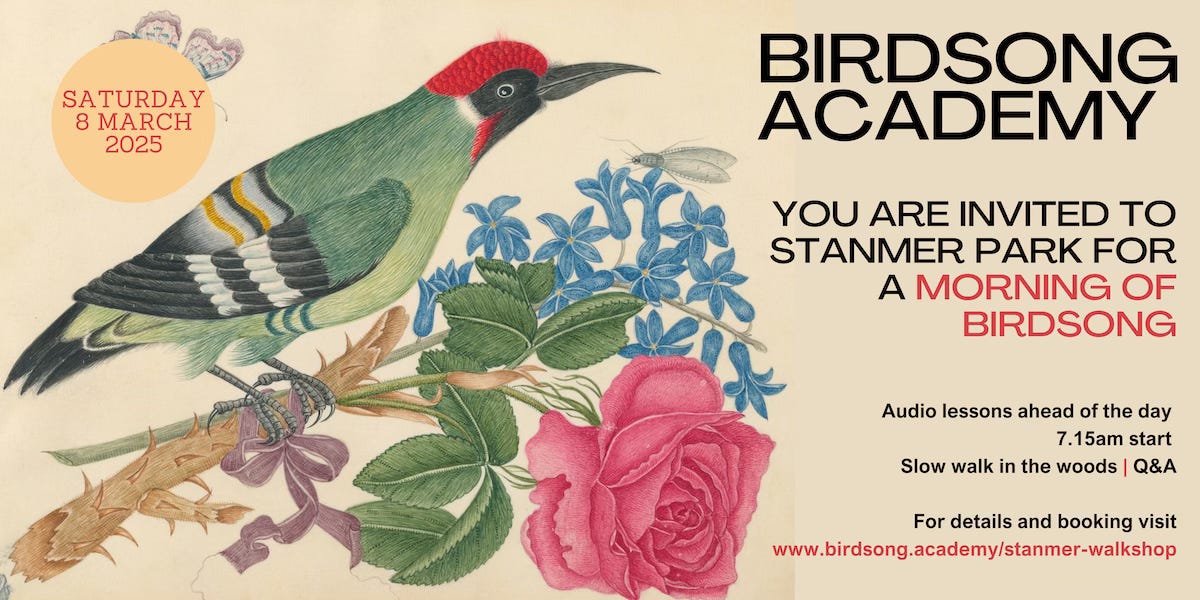

We’ll be listening for both goldcrests and firecrests at Stanmer Park on 8 March (see below), and also at Content Rising, a one-day gathering at the Millennium Seed Bank in West Sussex on 12 June 2025.

If you are interested in finding creative ways to communicate on some of the biggest challenges of our times - climate change, nature recovery, and inclusive cultures - take a look at the brilliant lineup of speakers and consider joining a day of inspiration, connection and rejuvenation (and firecrests) in the nature-rich grounds of Wakehurst Place.

🐦⬛ Birdsong walks this spring

Rye Harbour Nature Reserve (East Sussex) on Sunday 2nd March (Sussex Wildlife Trust event). TICKETS HERE

Stanmer Park, near Brighton on Saturday 8 March. TICKETS HERE

This is the eighth instalment in 2025’s cycle of Shriek of the Week. You can catch up with Robin, which includes details of the plan for this year, as well as Wren, Song Thrush, Blackbird, Great Tit, Dunnock and Chaffinch.

If you can, subscribing to the paid tier to Shriek of the Week supports me to write more and keep this all going.

It also gets you access to the full A-Z archive of Shriek of the Week AND our livestream-hopping Early Bird Club call - the next is 8am GMT on Saturday 1st March.

Media credits:

Thanks to Fintan O’Brien for his recording of goldcrest song and TheOtherKev on Pixabay for his image of a goldcrest

Firecrest image by Kiril Gruev from Pexels

Share this post